Against Lotteries

Tagged:CatBlogging

/

Investing

/

Math

/

SomebodyAskedMe

/

Statistics

Years ago, somebody asked me (an office mate, actually) about lottery tickets when the return was positive. Generally, lottery tickets are meant to lose money for you on average. So speaking only of money, you shouldn’t buy them. But once in a long while, they have a positive expected return. Should you buy one of those? Still no.

A Lottery Ticket Model, Oversimplified

Let’s consider an oversimplified model of a lottery ticket:

- You can buy one for price P0.

- With (very small!) probability p, it will pay you back P. (Of course, P>P0.)

- With (very likely!) probability 1−p, it will pay you back nothing.

That is, it’s sorta like a loaded coin flip that comes up heads p fraction of the time. Stats folk call this a Bernoulli distribution, the simplest of all possible distributions:

{Pr(flip = heads)=pPr(flip = tails)=1−pIf you win, you get a net pay off of P−P0; if you lose, you get −P0. Your rate of return is then the payoff divided by P0. Let ρ=P/P0, i.e., the ratio of the jackpot to the ticket price. Of course ρ>1. Then the distribution of returns R is:

{Pr(R=P−P0P0=ρ−1)=pPr(R=−P0P0=−1)=1−pThat’s the distribution, so let’s get the mean and variance (worked out pedantically, so this can be more of a tutorial than the way a professional would do it):

E[R]=p(ρ−1)+(1−p)(−1)=pρ−p−1+p=pρ−1σ2[R]=E[(R−E[R])2]=p(ρ−1−pρ+1)2+(1−p)(−1−pρ+1)2=p(1−p)2ρ2+p2(1−p)ρ2=p(1−p)ρ2(1−p+p)=p(1−p)ρ2σ[R]=√p(1−p)ρ(As a check on our work: we note that the Bernoulli distribution’s variance is p(1−p), so our answer for σ2 should be just a scaled version of that, which is what we have.)

Armed with E[R], we can determine when the expected payoff is positive:

E[R]>0⇒p>1/ρ or p>P0/PSo if you know the price P0, the payoff P, and the probability of winning p is larger than that, then the expected return is positive.

Should you buy a lottery ticket when that happens?

Return and Risk

Still no.

Consider the standard deviation above. This gives you an idea of how much the returns will vary, i.e., it warns you that even with a positive expectation you still have to buy an enormous number of tickets to win.

Let’s make that more quantitative.

In the investment world, there’s always a way to compare a potential investment against a safe investment. The safe investment has σ=0, i.e., no risk whatsoever. Hence its return R0 is small, but still safe.

- An example might be a US Treasury Bill, which pays you back your purchase price plus a small premium after 3, 6, 9, or 12 months.

- For longer periods you might consider TIPS Strips, which take inflation-protected Treasury bonds and convert them into a zero-coupon derivative: after a few years, you get back your inflation-corrected purchase price plus some inflation-corrected interest.

We’d like to know for an investment with expected return E[R] and risk σ[R] whether the extra return is worth the extra risk.

For this, there’s something called the Sharpe Ratio:

S=E[R]−R0σ[R]=pρ−1−R0√p(1−p)ρ- The numerator tells us how much more return we’re getting over the safe alternative. Needless to say, if this is negative you should walk away. You’re getting risk that you could completely avoid by using the safe investment, and make more money as well!

- The denominator is the measure of risk, i.e., the standard deviation in the return.

- We’d like the return to be high and the standard deviation to be low, so the ratio

compares them.

- Since numerator and denominator are in the same units, the ratio is dimensionless.

- A positive Sharpe ratio means we’re getting more return than the safe investment.

- A large positive Sharpe ratio tells us how much extra return we’re getting per unit of risk being taken.

So there are 3 hurdles to clear before we should consider a lottery ticket investment:

- As above, is the expected return positive? If not, walk away.

- Is the expected return above the safe alternative (say, a 3 month T-bill)? If not, walk away.

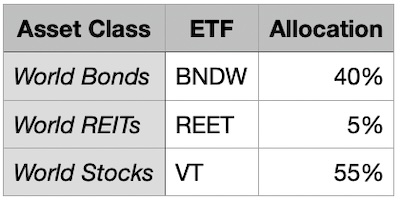

- Is the Sharpe ratio significantly higher than we could get (say, a portfolio of index funds 40% in world bonds BNDW, 5% in world real estate REET, and 55% in world stocks VT)? If not, walk away.

Let’s examine a concrete example. We’re going to look at the Massachusetts Mega-Millions lottery, chosen more for convenience and our Massachusetts chauvinism, than anything else. We’ll assume the jackpot is never shared, i.e., there is always 1 winner (not actually the case). Furthermore, we’ll simplify it down to just the maximum jackpot, ignoring all the smaller returns. (Those are present mostly to tease you into thinking you’re making progress, not to be an actual reward. They complicate the analysis, without being illuminating. Games, like investments, that are made complicated by the seller are not made complicated to be in your favor!)

Their web site as of 2024-Dec-14 gives us the following parameters:

- The cost of a ticket is $2.

- The current estimated jackpot is “approximately” $740 million.

- The chance of winning is 1 in 302,575,350.

Hence:

{ρ=P/P0=7.4×10+8/2=3.7×10+8E[R]=pρ−1=3.7×10+8⋅3.3×10−9−1=0.221Interesting! This is positive, so we pass hurdle 1. Each lottery ticket looks like it has the lofty return of 22%!

It also passes hurdle 2, since the Treasury reports that on 2024-Dec-13 the coupon-equivalent yield on a 1-year Treasury was:

R0=0.0424Since our lottery ticket’s E[R] comfortably exceeds that, we can consider it further as it will have a positive numerator in the Sharpe Ratio.

But what’s the Sharpe Ratio of this lottery ticket? We need the standard deviation to calculate that:

{σ[R]=√p(1−p)ρ=√3.3×10−9⋅(1−3.3×10−9)⋅3.7×10+8=21,254.88S=(0.221−0.0481)/21254.88=8.1×10−6This is tiny! In it’s offering you a few parts per million of “extra” return in exchange for each additional percent of risk, which is absurd. The source of the absurdly small S here is the ginormous standard deviation σ. (Also, if we were to take a more careful approach and estimate error bars on S, it would be statistically indistinguishable from 0 or even negative values.)

For comparison purposes, let’s consider the portfolio of world bonds, world real estate,

and world stock alluded to above. Using

Portfolio Visualizer,

I am reliably informed that using 2023-2024 data the Sharpe ratio is:

For comparison purposes, let’s consider the portfolio of world bonds, world real estate,

and world stock alluded to above. Using

Portfolio Visualizer,

I am reliably informed that using 2023-2024 data the Sharpe ratio is:

Now, to be sure, it was a pretty good year! (A more typical value would be 0.4 - 0.5.) But it’s literally about a million times better than the lottery ticket, in terms of return over the safe asset per unit of risk taken!

The lottery ticket is a terrible, terrible choice. The alternatives are easily available. You can much more sensibly invest, as shown here, in human economic activity of all sorts, all over the world.

Paths Not Taken

Of course, there are many other risk-adjusted return metrics with which to evaluate investment opportunities: using Sharpe ratio with downside risk only (semi-variance), the Treynor Ratio (comparison to stock market risk β), the Modigliani risk-adjusted measure (leverage/cash dilution to match the market), the Sortino ratio (with respect to a hurdle rate, or required return, and using semi-variance), and many others. Also, there are many other approaches which do not use mean and standard deviation, but either use a non-normal distribution, or are parametric in nature, or take a totally different Bayesian approach.

We’ve used all of those at one time or another, but here chose the Sharpe ratio because we understand what it means, it is widely used, and readily interpretable.

The Weekend Conclusion

We have derived a formula for the Sharpe ratio (extra return per unit risk taken) for a lottery ticket. With ticket price P0, payoff P, probability of winning the payoff p, and safe return of something like a short term Treasury R0:

{ρ=P/P0S=pρ−1−R0√p(1−p)ρThe economic argument against lottery tickets is 3-fold:

- The expected return is almost always negative.

- When the expected return is positive, it is still often less than safe investments.

- When the expected return exceeds safe investments, the Sharpe ratio is miserable compared to easily assembled investment portfolios. That is, you’re getting offered miserably small amounts of profit for taking enormous risks.

The moral argument against lottery tickets is less mathematical, bu also compelling:

-

I believe we have a moral duty serve society, making the world better for our presence in it. This is true even if the task seems hopelessly daunting:

It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you at liberty to neglect it… – Pirkei Avot 2:16 (Talmud).

Lotteries do not do this. Investing in the general welfare of all humanity does do this. One way we can do this is by choice of a good occupation, a good spiritual life, and a good community & family life. Another way is by investing in the progress of all humanity, as the portfolio above.

-

We must not attempt to gain simply by taking value from others, allegedly by being smarter in a gambling “game”. That’s using your intellectual stiletto to cut the wallet out of others clothes, steal their money, leave them nothing.

You’ve hoisted the Jolly Roger, and thereby declared your intent for piracy. Don’t be surprised when I show you the disrespect this decision merits. When you eventually go broke, I will be minimally sympathetic (“without some scot of penitential tears”, approximately quoting Beatrice’s final requirement of Dante in Il Purgatorio, Canto XXX, LL 144-145; of course repentance earns great credibility and forgiveness).

The Weekend Publisher and the Assistant Weekend Publisher, shown here, agree. There are far more profitable & interesting things in life than lottery tickets!

(Ceterum censeo, Trump incarcerandam esse.)

Notes & References

Nope.

Gestae Commentaria

Comments for this post are closed pending repair of the comment system, but the Email/Twitter/Mastodon icons at page-top always work.