Does Education Help Against Anti-Semitism?

Tagged:JournalClub

/

Politics

/

Religion

/

Sadness

/

Statistics

Does more education help in prying people loose from antisemitism? Frustratingly, “it depends.”

Education vs Antisemitism

Back when I was just a wee child, I never thought much about antisemitism. That’s partly because in a small, semi-rural midwestern town there were only a few Jews, all of whom were culturally indistinguishable from everybody else. Also, in those days, it was permissible to think that antisemitism was mostly an issue of the past, largely settled in World War II with the defeat of the Nazis. In my naïveté I thought antisemitism a thing largely of the past, or of the stubbornly uneducated.

It was much in the same sense as we thought of racism: in a mostly-white small town, racism was not a daily issue for whites, and could be regarded as having been settled by the Civil War.

We were, of course, wrong about both. Racism, post the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, was no longer a de jure matter, but it was most certainly and viciously still present.

So too with antisemitism. And, right on time, the Republicans are now spouting some deeply antisemitic rhetoric.

So one might ask the usual question we liberals ask: isn’t just a little bit more information, a little bit more education, the answer to our problems? We always ask this, but sadly trip over multiple obstacles:

- The Dunning-Kruger effect means that the ignorant are full of unearned confidence in their opinions, often feeling no need for further information.

- The Backfire effect often means people are threatened by information that might change their beliefs, and respond by digging in deeper and tighter in their ignorant positions.

So it might go either way: does education help or hurt the anti-antisemitism project?

What the Data Says

The inspiration for today’s post comes from an article in

Research & Politics [1] that discusses exactly this.

The inspiration for today’s post comes from an article in

Research & Politics [1] that discusses exactly this.

They study a level of antisemitism in a sample of people, by responses to a survey that gauges how often (bad) stereotypes about Jews are confirmed. However, there’s a twist:

- They do this world-wide in over 100 countries, stratifying the antisemitism results by country.

- Then they note for each country whether it had endorsed UN resolutions condemning Holocaust denial (UN General Assembly, Session 61, agenda item 44, on Holocaust denial, 2007-Jan-23) and condemning antisemitism (UN General Assembly: Joint Statement against Antisemitism, 2015-Jan-22).

It turned out that the effect of education on antisemitism depended strongly on the national context, getting better in countries that signed on to the antisemitism resolutions and worse in those that did not (emphasis added):

It is commonly argued that education promotes greater openness and political diversity and decreases prejudice (Golebiowska, 1995). For example, previous research finds that higher levels of education are associated with reduced prejudice and outgroup hostility (e.g., Borgonovi, 2012; Easterbrook et al., 2016). These findings suggest that education can challenge prejudice and promote critical thinking and tolerance.

However, education can also promote intolerance in illiberal states, especially if teaching or curricula promote or reinforce negative views about outgroups (Zhang and Brym, 2019). For example, Saudi textbooks were found to contain antisemitic and anti-Western stereotypes after the 9/11 terrorist attacks (O’Hara, 2006).

I’m not going to go through all their data cleaning and modeling, because, frankly, they did not supply any information to support that. Their entire paper, including the supplement, contain not even a single equation! I just don’t get why people think they can get away with that. Sigh.

So, we have little recourse than to trust, provisionally, the analysis they did and which they described in a barrage of word salad that I decline to attempt to decrypt.

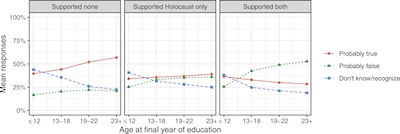

Here’s their Figure 1, showing their main result:

Here’s their Figure 1, showing their main result:

- The leftmost graph is for countries that rejected both resolutions (the most antisemitic nations), the middle for those that supported only one, and the right for the countries that supported both (the least antisemitic nations). For our purposes, let’s just look at the leftmost and rightmost graphs, to get an idea of the range of the effect of antisemitism in the host culture.

- The horizontal axes are age at final year of education, so less educated people are on the left of each graph, and more educated people on the right.

- There are 3 curves: red for people who think the antisemitic stereotypes are mostly true, green for those who think they’re probably false, and blue for those who don’t have a clue.

Let’s state our Null Hypothesis (since the authors failed to do so!). In an ideal world where education discouraged antisemitism, we’d expect to see:

- the red curves fall (agreement with antisemitism falls with education),

- green curves rise (disagreement with antisemitism rises with education), and

- blue curves fall (ignorance decreases with education).

Now, what do we actually see?

- This is the situation we see on the right. In countries whose cultures do not encourage antisemitism, education works.

- However, it is not the situation we see on the left, in the countries with more antisemitic cultures. While the blue curve does fall (ignorance of the issues decreases), the green curve is flat (disagreement with antisemitism not influenced by education), and the red curve rises (more education leads to more agreement with antisemitism).

In other words, education in an antisemitic culture confirms the antisemitic beliefs of those being educated.

Also, in no case do the curves move a lot, i.e., best case we have 50% of the highly educated citizens of less antisemitic countries disagreeing with antisemitism (green curve, rightmost graph).

The Weekend Conclusion

It’s enough to make me despair. (Though, to be honest, given the state of the world, that doesn’t take much nowadays.)

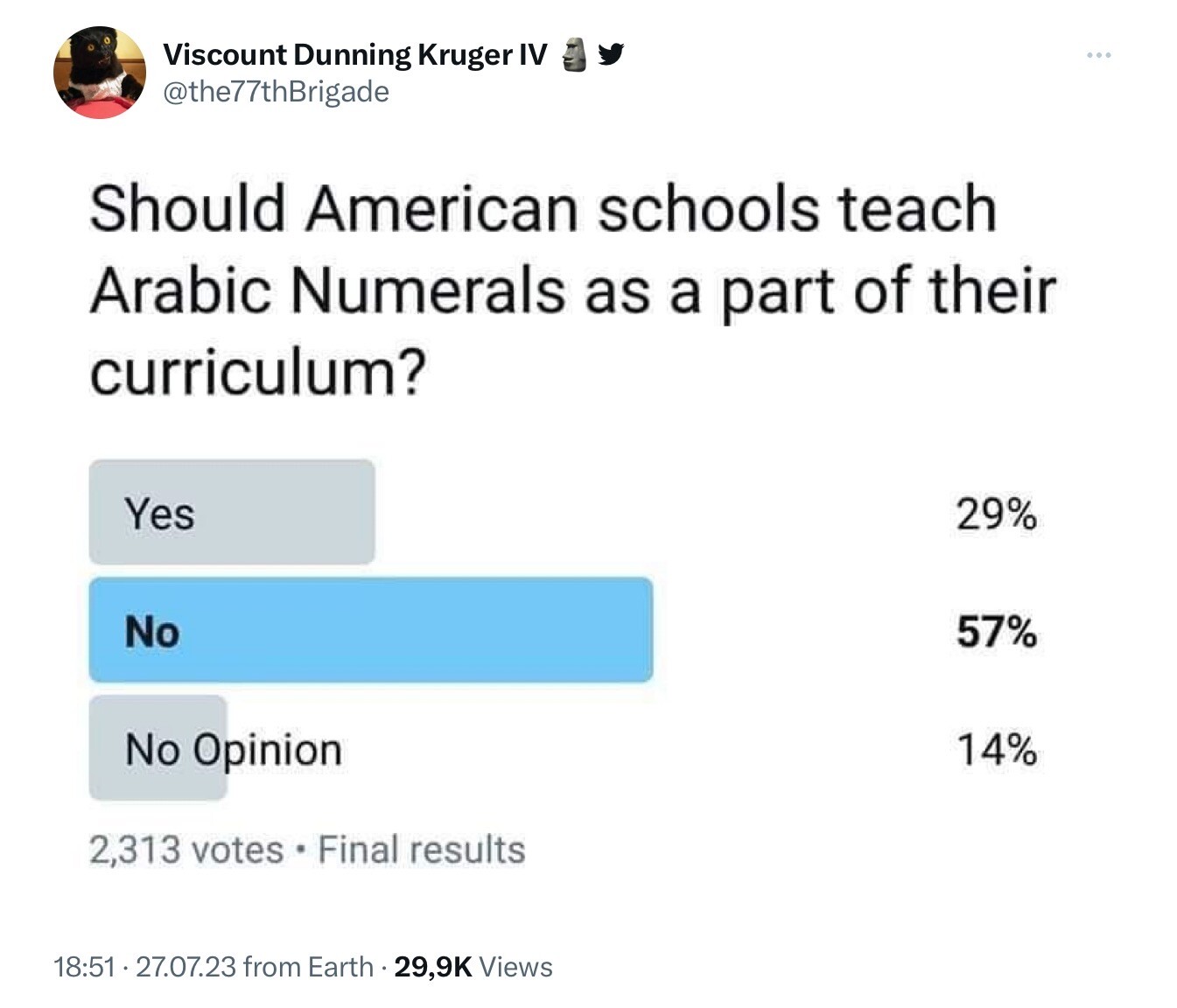

And it’s not as though we’re immune to this effect in the Western, developed, somewhat

less antisemitic nations. This tweet humorously summarizes

a survey by Civic Science from 2019

showing the allergic reaction Americans had to the phrase “Arabic numerals” to describe 0,

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

And it’s not as though we’re immune to this effect in the Western, developed, somewhat

less antisemitic nations. This tweet humorously summarizes

a survey by Civic Science from 2019

showing the allergic reaction Americans had to the phrase “Arabic numerals” to describe 0,

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

And lest anyone think this sort of conclusion-jumping is only on the right (though maybe it’s mostly on the right?), a similar prejudice was expressed against the “creation theories” of the French Catholic priest Lemaître. That phrasing is full of bait to make one suspect the usual conservative religious creation theory crap; in fact Georges Lemaître, while genuinely a French Catholic priest, was also a physicist involved in the application of General Relativity to the theory of an expanding universe and ultimately the Big Bang. It doesn’t get any more respectable than that. So the suspicion was just my tribe’s deep, and well-earned suspicion of religious nuts messing with education.

It’s as though some part of our minds, mired in the Dark Ages, wishes to use the Dark Arts of persuasion to inflict the prejudices of our forebears on our offspring.

Maybe try very hard not to do that?

(Ceterum censeo, Trump incarcerandam esse.)

Notes & References

1: B Nyhan, S Yamaya, and T Zeitzoff, “How the relationship between education and antisemitism varies between countries”, Research & Politics, 11:2, 2024-Jun-17. DOI: 10.1177/2053168024126. ↩

Gestae Commentaria

Comments for this post are closed pending repair of the comment system, but the Email/Twitter/Mastodon icons at page-top always work.