Good News on HIV Prevention

Tagged:CorporateLifeAndItsDiscontents

/

JournalClub

/

MathInTheNews

/

PharmaAndBiotech

/

Statistics

Good news on preliminary Phase 3 readout of lenacapavir: 100% efficacy in preventing infection!

HIV Prevention Meds: Why a New One?

There are already preventive medications for HIV, called pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PReP medications. There are 2 problems with the existing PReP meds:

-

Human nature: They require taking meds every day. Most people simply cannot do that with perfect regularity, despite encouragement.

In fact, in some communities there is apparently a social stigma attached to taking PReP daily, implying one might have HIV or other sexual partners. Trust NT social games to apply social pressure in exactly the wrong direction!

-

Not 100% efficacy: They’re not perfect. Maybe 99% prevention [1], but not 100%. There are fewer bullets in the gun, but it’s still Russian roulette. Once you know the game is Russian Roulette, the only correct strategy is to put down the gun and walk away.

We can’t fix human nature, so the hunt is on for the other one: better meds with 100% efficacy & fewer chances for people to screw up taking their meds.

A Preliminary Readout on the Lenacapavir Trial

From NPR [2] comes a report of good news on that front.

From NPR [2] comes a report of good news on that front.

Gilead is testing lenacapavir (commercial name “Sunlenca”) [3], the amusingly battleship-sized molecule shown here. (Med chemists are the best!)

It’s a capsid inhibitor that interferes with the HIV viral capsid subunits required to assemble and release the virus. It’s even already approved as part of some HIV therapies, so the safety issues have been well studied.

What’s interesting is that it’s now being studied as an improvement on PReP for prevention: both whether it has better efficacy than PReP, and whether we can get better patient compliance.

The initially counterintuitive aspect here is that lenacapavir is an injectable, whereas PReP regimens are oral (just pills, basically). You should almost always prefer oral to injectable to get good patient compliance, because people hate shots but hate pills slightly less. However, lenacapavir only requires injections twice a year, so it can overcome the stupid social stigma attached to taking PReP pills daily. Clever!

Alas, the NPR article is maddeningly short on details, with few if any links to primary

sources. So we had to dig a bit into the unfortunate world of corporate press releases.

Normally we spit when contemplating these, as they are unreliable. But… the trial

hasn’t been published (or peer reviewed) yet, so this is all we’ve got. Also, there are

severe penalties for misrepresenting results, so we can rely somewhat on fear to push

toward truth.

Alas, the NPR article is maddeningly short on details, with few if any links to primary

sources. So we had to dig a bit into the unfortunate world of corporate press releases.

Normally we spit when contemplating these, as they are unreliable. But… the trial

hasn’t been published (or peer reviewed) yet, so this is all we’ve got. Also, there are

severe penalties for misrepresenting results, so we can rely somewhat on fear to push

toward truth.

Gilead’s press release [4] is slightly more informative, though full of the usual self-serving language. Their clinical trial page [5] doesn’t appear to tell us much we want to know, other than this is the trial registered with the US government as NCT04994509. It’s a Phase 3 trial, i.e., where the serious money gets put down before submission to regulatory bodies for approval.

This trial is called PURPOSE 1, and is exclusively for women in sub-Saharan Africa. Yes, sub-Saharan Africans are only 10% of world population, but they’re also nearly 2/3 of people living with HIV, according to NPR. Also, teen girls and young women get infected at a rate of about 4000/week! So it’s a very good test population for a trial about preventing transmission. There are other “PURPOSE” trials [6], still in progress, with similar names:

- Phase 3 PURPOSE 2, for cisgender men who have sex with men, transgender men, transgender women and gender non-binary individuals who have sex with partners assigned male at birth in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, South Africa, Thailand and the United States.

- Phase 2 PURPOSE 3, for PReP in cisgender adult women in the United States.

- Phase 3 PURPOSE 4, for injectable drug users in the United States.

After wading through the word salad so beloved by corporate PR folk and reporters, we can finally glean some actual relevant evidence about the preliminary data on PURPOSE 1. It’s described as double-blind, though I have a hard time with that: surely patients and clinicians can tell if they’re taking a pill vs getting an injection, so how can that be blind?

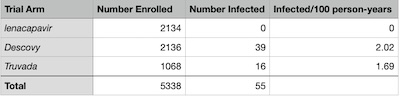

The approximately 5300 patients were randomized in ratio 2:2:1 to get lenacapavir,

Descovy, or Truvada (the latter 2 being the existing PReP medications used as standard of

care controls). The exact numbers, taken from the press release, are in the table shown

here.

The approximately 5300 patients were randomized in ratio 2:2:1 to get lenacapavir,

Descovy, or Truvada (the latter 2 being the existing PReP medications used as standard of

care controls). The exact numbers, taken from the press release, are in the table shown

here.

Gilead points out the difference in infections per 100 person-years, and asserts p≤10−4 without showing their work or even citing the test. (This is why we despise corporate press releases, because they make claims without any hope of enabling peer review! Or even any hope of figuring out what they’re talking about, for that matter.)

Of course, lacking censorship data about when patients dropped out, we can’t say anything definitive like the trial authors will eventually have to do. But we can do a few approximate things, just with the patient counts above, and check that this more or less makes sense. So we wrote a little R script [7] to do exactly that!

Efficacy Compared to PReP Controls

First, we can treat the trial using the PReP arm(s) as a simple control vs lenacapavir. That lets us calculate an efficacy by:

Efficacy=100%×(1−Pr(infect|lenacapavir)Pr(infect|PReP))Of course, since the number of infections in the lenacapavir arm was 0, the efficacy will

always be 100%. However, we can use statistics to get a 95% confidence interval on that.

Here we used the relatively naive binomial confidence intervals calculated by

ciBinomial() in R package gsDesign. (A sophisticated method would use

the Bayesian posterior Beta ratios for which we did the math some years ago,

but have not written the R package to implement it numerically.)

Conclusion: The efficacy of lenacapavir in comparison to PReP was 100%, with 95% confidence limits of 89.53% – 100.0%. That is, we’ve removed 89% – 100% of the remaining risk incurred by the PReP patients.

Quite good!

Statistical Significance & Strength of Effect

Another approach, still frequentist, would be to assess whether lenacapavir is statistically significantly better than PReP (“Is the effect real: likely to reproduce if we did the experiment again?”) and what its strength of effect is (“If it’s real, then is this a big deal or a little deal?”).

For significance, we used a test of proportions: are the 2 arms different enough in the proportions infected to be believable? We applied a Yates continuity correction (mostly because that was the default; we’re happy to take advice on this subject).

Conclusion: The test got p∼2.75×10−9, i.e., very statistically significant indeed. The difference in proportions infected had a 95% confidence interval of [−0.022,−0.012], nicely bounded away from 0. The difference in infection rates is definitely real.

For strength, we used Cohen’s h as our measure. If p1 and p2 are the 2 infection probabilities in the 2 arms, then:

h=2×(arcsin(√p1)−arcsin(√p2))Since we’ll consider it in absolute value, the range of h is [0,+π]. By convention, a value of 0.2 is “small”, 0.5 is “medium”, and 0.8 is a “large” effect.

Conclusion: We find |h|=0.263. It’s not a big effect. But also keep in mind that the infection rate under PReP is only 1.7% vs lenacapavir’s 0% – there’s only so much room for improvement, anyway! This results achieves the maximum effect possible by observing 0 infections in the treatment arm.

So we have a real effect which is as large as possible, given the very good efficacy of PReP by itself.

Bayesian Posteriors on the Probability of Infection in Each Arm

Now let’s think a bit like Bayesians:

-

We assume, in each arm i, the number of infections ki is binomially distributed with some unknown parameter pi representing the probability of infection under that arm:

Pr(ki|Ni,pi)=(Niki)pki(1−pi)N−k - Assume our prior beliefs about pi are uninformative, i.e., pi∼Uniform(0,1). Not entirely coincidentally, we note that this uniform distribution is also a Beta(1,1) distribution.

-

Then a bit of Bayesian algebra tells us that after observing a trial with Ni people and ki infections, our posterior on pi should be a Beta(ki+1,Ni−ki+1) distribution:

Pr(pi|Ni,ki)=pkii(1−pi)Ni−ki+1B(ki+1,Ni−ki+1) - Armed with that posterior, we can do all sorts of things:

- A plot will reveal our posterior beliefs and uncertainties about the pi’s.

- And of course we can calculate quantiles.

- Hardcore Bayesians, when pressed to give a point estimate, will pick the mode of this distribution, hence a MAP estimator (Maximum A posteriori Probability). That has a couple nice properties under transformations. (E.g., the mode of the tranformed distribution is the transform of the mode. This is not true of either the median or the mean.)

- However, your humble Weekend Editor hates modes, and vastly prefers medians. Especially if we’re not going to do any further transformations! So, a median A posteriori Probability, or “mAP estimator” might be a silly name for it. (Don’t bother learning it; nobody uses this name!)

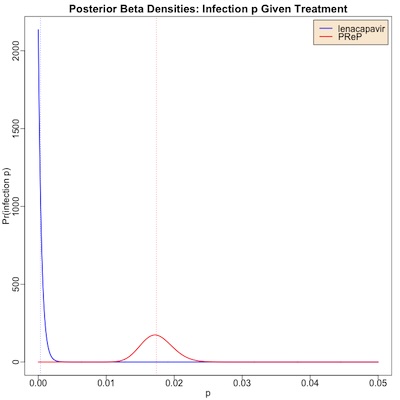

We find the infection mAP estimators and their 95% credibility intervals to be:

- lenacapavir: 0.032% (CL: 0.001% – 0.173%)

- PReP: 1.74% (CL: 1.32% – 2.23%)

(The Bayesian analysis gives a worst-case – upper end of the CL – infection rate of 0.173% for lenacapavir. The corresponding frequentist heuristic for when no events are observed, the venerable Rule of 3, gives a comparable worst case of 0.141%. Both say there’s a worst case chance of just over 1 in a thousand of infection, which is both consistent and a very good result.)

The plot here shows the posterior distributions:

The plot here shows the posterior distributions:

- The red curve is for PReP, the standard of care. It has a bump at around 1.7% for infection probability, but we could credibly believe from this trial (Bayesian “credibility interval”) that it’s anywhere from 1.3% – 2.2%. The vertical red dashed line is at the median value of 1.74%.

- The blue curve is for lenacapavir.

- Note that even though 0 infections were observed, we still have a finite, but small, infection probability. This is what Bayes methods do: they pull our prior belief of uniform probability into a pile up against 0, though with a teensy bit of a right tail.

- Still, it’s really tiny: 0.032% is the median, with a credible interval of 0.001% – 0.173%.

- The vertical blue dashed line shows the median value of 0.032%.

Conclusion: The Bayesian posteriors on the infection probability are quite different in the 2 arms (0.032% vs 1.74%), and very much in favor of lenacapavir.

Given that PReP was a very good prophylaxis therapy to start, this is as good news as it is mathematically possible to get.

Some Real-World Questions

But in the real world, nothing is ever allowed to be simple, right?

Realism on Cost

NPR points out a major problem with relative costs of lenacapavir vs PReP:

Any eventual approval and widespread use would come with challenges. According to an analysis presented at the 24th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2022), PrEP medications would need to cost less than $54 a year per patient for South Africa, for example, to afford them. Lenacapavir’s cost as HIV treatment in the United States in 2023 was $42,250 per new patient per year. Oral PrEP options, on the other hand, can cost less than $4 a month.

So it appears, in order to get effective levels of uptake in Africa (and really, anywhere else, for that matter) they need to reduce the cost of 2 injections/year by about a factor of 1,000x. That’s… more than a little bit daunting.

Gilead has apparently responded to these concerns with another press

release. [8] Now, big piles of word salad in corporate-speak

are Not My Favorite Thing. So wading through this for evidence of a plan was tedious.

Gilead has apparently responded to these concerns with another press

release. [8] Now, big piles of word salad in corporate-speak

are Not My Favorite Thing. So wading through this for evidence of a plan was tedious.

It appears that they wish to avoid what is known as “compulsory licensing”, in which countries force them to license to generic makers who will make it cheaply. They wish to avoid this by:

- Ensuring dedicated Gilead supply in the countries where the need is greatest until voluntary licensing partners are able to supply high-quality, low-cost versions of lenacapavir, and

- Developing a robust direct voluntary licensing program to expedite access to those versions of lenacapavir in high-incidence, resource-limited countries. We are moving with urgency to negotiate these contracts.

Basically: make lots of it available, and seek out voluntary licensing in low-income countries. That leads to the question of who’s going to block the export from low-income to medium- and high-income countries, but that’s for another day.

Perhaps there’s more in the press release, beyond the point where I could bear to read.

This is maddeningly vague, but I dunno what exactly a detailed plan for availability at $54/yr would look like, either. Maybe we give them the benefit of the doubt for now, and yell at them a year after approval if the situation is still $42,250 vs $54?

‘Efficacy’ vs ‘Effectiveness’

Also: it’s important to remember that Phase 3 clinical trials are (almost) ideal conditions. There’s always somebody to supervise, and verify that people take their meds. And they usually do their job.

On the other hand, in actual practice, people forget to take their medications, they’re given stupid amounts of peer pressure to take more or less of it, they maybe can’t afford it, and all kinds of other things. Stuff works less well under those circumstances.

Unsurprisingly: medicines work when you take them, and don’t when you don’t.

So we have 2 words: ‘efficacy’ is how well something works under ideal conditions, whereas ‘effectiveness’ is how well it works under ordinary, real-world, battlefield conditions.

What we’ve seen here is that lenacapavir has startlingly good efficacy, under trial conditions. It’s effectiveness in the hands of patients and their doctor under normal practice is unknown. However, the fact that it’s just a twice-yearly injection inspires hope that doctors can remind patients enough to keep them on schedule. Or so one may hope.

The Weekend Conclusion

Keep in mind that everything we’ve done above is based on just 4 lousy integers: the patient counts and infection counts in 2 arms. That’s all they’ve reported, and without detailed data including censorship we can’t proceed further to the more principled Cox regressions. So we’re somewhat overstating the case for lenacapavir here.

However, this is unambiguously good news, even with this approximate analysis. It’s so good, in fact, that according to NPR they stopped the clinical trial and just offered everybody lenacapavir (emphasis ours):

These results were significant enough for the Data Monitoring Committee — an independent group of experts appointed to assess the progress of clinical trials — to recommend that Gilead halt its blinded trial and offer lenacapavir to all study participants. On June 20, Gilead announced these results, and now, all participants can choose to receive the injection.

It happens somewhat rarely that a treatment is so unambiguously good that the safety folk just stop it and say “Game over, just give everybody That New Stuff, right the hell now.” I’ve seen it happen before, but it’s definitely not the rule.

In a world with so little good news, we should hold onto these moments.

(Ceterum censeo, Trump incarcerandam esse.)

Notes & References

1: US CDC Staff, “Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)”, US CDC web site, downloaded 2024-Jul-11. ↩

2: MIB Guinle, “A new way to prevent HIV delivers dramatic results in trial”, NPR, 2024-Jul-03. ↩

3: Wikipedia Editors, “Lenacapavir”, Wikipedia, downloaded 2024-Jul-11. ↩

4: Gilead Staff, “Gilead’s Twice-Yearly Lenacapavir Demonstrated 100% Efficacy and Superiority to Daily Truvada® for HIV Prevention”, Gilead Press Releases, 2024-Jun-20.

NB: This is clinical trial NCT04994509, as registered with the US government at clinicaltrials.gov.↩

5: Gilead Staff, “Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Study of Lenacapavir and Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide in Adolescent Girls and Young Women at Risk of HIV Infection (PURPOSE 1)”, Gilead web pages, retrieved 2024-Jul-11. ↩

6: PURPOSE Clinical Trial Staff, “Prevention with PURPOSE”, PURPOSE clinical trials page, downloaded 2024-Jul-11. ↩

7: Weekend Editor, “R script for preliminary analysis of PURPOSE1 trial”, Some Weekend Reading blog, 2024-Jul-11.

There is also a transcript of running this available, so you can check the outputs.

Some utility scripts are also used, which are available from your humble Weekend Editor upon request. ↩

8: Gilead Staff, “Access Planning in High-Incidence, Resource-Limited Countries for Lenacapavir for HIV Prevention”, 2024-Jun-20. ↩

Gestae Commentaria

Comments for this post are closed pending repair of the comment system, but the Email/Twitter/Mastodon icons at page-top always work.