Are the Trump Government Firinigs Politically Targeted?

Tagged:MathInTheNews

/

Politics

/

Sadness

/

Statistics

Are the federal government firings by Trump/Musk/DOGE random, or in large departments, or politically targeted regardless of merit? It turns out there’s evidence to decide this objectively.

The Question: Trump Government Firings vs Ideology

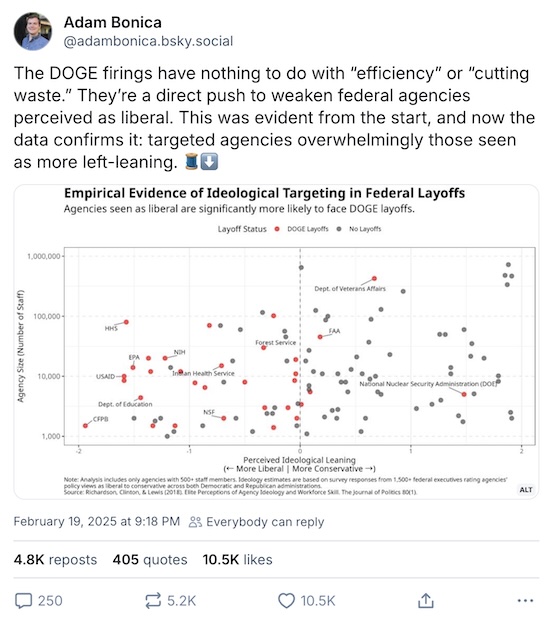

Stanford political scientist Adam Bonica made a remarkable post on Mastodon [1] in which he argued that the Trump/Musk/DOGE firings are not at all directed at saving government expenditures, as advertised. Instead, they are ruthlessly politically targeted at agencies which are perceived as liberal.

It’s not about saving money. It’s about finding anything liberals like, and burning it to the ground.

So here’s what he did:

- He used a paper by Richardson, Clinton, and Lewis from 2018 [2] to get a score for the perceived liberal/conservative agenda of numerous federal agencies. That paper is based on responses from > 1500 federal executives, rating agency policy views as liberal to conservative. It was collected across both Republican and Democratic administrations. There might be problems with it, but it looks pretty good.

- Then he collected other data for those agencies, notably annual budget and headcount (above 500 persons; no point in looking at tiny agencies). It might make sense for the DOGE chainsaw to take a swing at big budgets and big headcounts, after all.

- Finally, he annotated each agency by whether or not there were DOGE layoffs, or whether the agency was targeted for dismantling, or both.

The plot above is one of his results: it shows there’s no particular relationship between agency size (vertical axis, log scale) and agency ideology (horizontal scale). However, coloring in the points by the presence of layoffs shows a clear bias to the agencies perceived as more left.

The Answer: Our Reanalysis of the Same Data

Ok, so you know what’s gonna happen next, right?

We got his data and wrote an R script [3] to reanalyze it in several ways, including what he did and several orthogonal ways, and with some improvements (like cross-validated, LASSO-regulated logistic regression).

Some Scatterplots: Does Anything Look Suspicious?

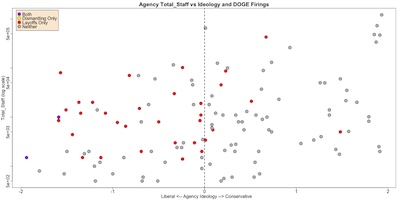

Here’s our attempt to reproduce Bonica’s plot above: agency staff size on a log scale vs

ideological score. It looks like he’s imposed some limits on the vertical axis, to limit

agency size to 1,000 to 1,000,000, so our plot shows a bit more at the top and bottom.

But other than that, we reach pretty much the same conclusion:

Here’s our attempt to reproduce Bonica’s plot above: agency staff size on a log scale vs

ideological score. It looks like he’s imposed some limits on the vertical axis, to limit

agency size to 1,000 to 1,000,000, so our plot shows a bit more at the top and bottom.

But other than that, we reach pretty much the same conclusion:

- DOGE firings look like they have little relationship to agency size. (The red/purple dots are about evenly distributed, vertically.)

- DOGE firings do, on the other hand, look like they are politically targeted on agencies that federal managers characterized as more liberal in outlook. (Most of the red/purple dots are on the left. The 2 purple dots that got a double-tap of layoffs and targeting for dismantling are USAID and CFPB, predictably.)

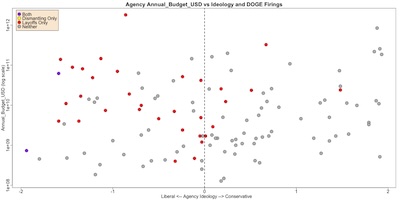

Here’s a similar plot, where the vertical axis is the agency budget on a log scale, and

the horizontal axis is the ideological score of the agency. Again, a similar conclusion:

Here’s a similar plot, where the vertical axis is the agency budget on a log scale, and

the horizontal axis is the ideological score of the agency. Again, a similar conclusion:

- DOGE firings look like they have little relationship to agency budget. (The red/purple dots are about evenly distributed, vertically.)

- DOGE firings do, on the other hand, look like they are politically targeted on agencies that federal managers characterized as more liberal in outlook. (Most of the red/purple dots are on the left.)

So they’re not going after the “big game” in terms of staff or budget, as one would expect if they were sincere about saving money: that’s where the money is spent, so that’s where you should look to save. Instead, it looks like they’re just on a witch hunt to burn down stuff they personally dislike.

More Objectively: Is It Statistically Significantly Suspicious?

Ok, that looks visually damning, but is it statistically significant?

Fisher’s Exact Test

We’ll start with a straightforward table of the number of agencies experiencing layoffs, targeting for dismantling, both, or neither vs whether the agency is left (score < 0) or right (score > 0). The data look like this:

Left Right | Row Totals

Both 2 0 | 2

Dismantling Only 0 0 | 0

Layoffs Only 25 7 | 32

Neither 30 59 | 89

----------------------------+-----------

Col Totals 57 66 | 123

It sure looks as if there’s more destruction being wrought in the lefty agencies. We can assess the statistical significance of this with a Fisher Exact Test (with or without the Lady Tasting Tea):

Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data

data: freqs

p-value = 1.076e-05

alternative hypothesis: two.sided

That tells us we got a p-value of p∼1.076×10−5. There’s only about a chance in 100,000 that the data would be this skewed toward left agencies when the truth was unbiased.

If we had narrowed this down to 2 rows – layoffs/dismantling or not – then we could have gotten an odds ratio out of the Fisher test, as a measure of strength of effect:

> tbl <- data.frame(Left = c(27, 30), Right = c(7, 59), row.names = c("Layoffs/Dismantling", "None")); tbl

Left Right

Layoffs/Dismantling 27 7

None 30 59

> fisher.test(tbl)

Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data

data: tbl

p-value = 5.945e-06

alternative hypothesis: true odds ratio is not equal to 1

95 percent confidence interval:

2.766889 22.708114

sample estimates:

odds ratio

7.45096

The p-value is even smaller, at p∼5.95×10−6.

The p-value is even smaller, at p∼5.95×10−6.

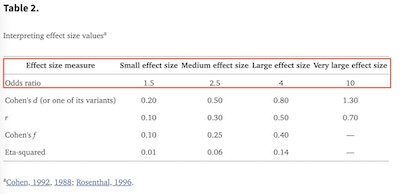

To interpret the odds ratio as effect size we consult Maher, et al. [4, Table 2 shown here] This is beyond what’s conventionally considered a large effect size.

In other words: the bias against left agencies is real (not an artifact of chance in this dataset), and large (not an inconsequential thing).

Some Regression Models

We can and should attempt more detailed regression models: can we use agency staff levels, budgets, and ideological scores to predict DOGE layoffs?

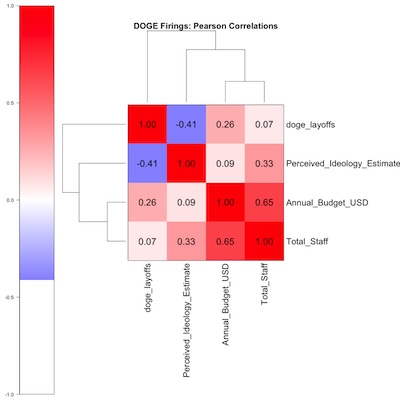

Before jumping into any multivariate regression model, I like to look at the correlation

matrix to see just how many independent things are going on, and whether any of them

relate to the dependent variable (DOGE layoffs or not) we’re trying to predict.

Before jumping into any multivariate regression model, I like to look at the correlation

matrix to see just how many independent things are going on, and whether any of them

relate to the dependent variable (DOGE layoffs or not) we’re trying to predict.

- First, note in the lower left that log budget and log staff size are correlated. This should not be surprising: big agencies have big budgets!

- Second, note the strong negative correlation between DOGE layoffs and ideological score (R∼−0.41). Again, unsurprising: negative/left score means they hate it and want to destroy it with layoffs and dismantling.

- Third, there’s at best a mild correlation between budget levels and DOGE layoffs (R∼0.26). There is practically no correlation with staff levels (R∼0.07). We already know they’re not particularly targeting the big game, so this is just quantitative confirmation of that.

- Fourth, note the negligible correlation between agency funding and agency

ideology (R∼0.09). There is absolutely no case to be made that the government

overfunds left-leaning agencies. The giant Department of Defense is a glaring example

of how much money is given to a right-leaning entity, regardless of how one feels about

defense spending.

- There is, however, some interesting positive news here: log budget is a partial predictor of DOGE layoffs, and is independent of ideology score. Independent predictors are always good to have.

Like good little statisticians, we should always state the outcome we expect before doing a calculation. So, here we expect regression to tell us that ideological score is the best predictor, followed by budget, and then maybe by staff. Indeed, under crossvalidation and LASSO regulation, the latter 2 variables might be ejected altogether from the model.

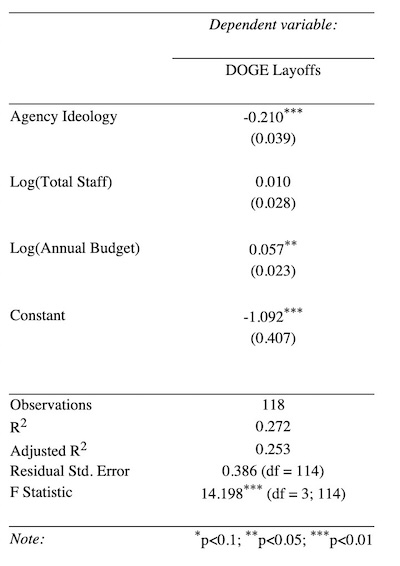

Bonica did a regression model, but it seems he used Ordinary Least Squares as a predictor, i.e. finding coefficients β0, β1, β2, and β3 to optimize prediction of DOGE layoffs in:

DOGE Layoff=β0+β1Ideology+β2log(Staff)+β3log(Budget) Here’s what he found, though he doesn’t specify with what software.

Here’s what he found, though he doesn’t specify with what software.

- On the one hand, it’s not a bad fit:

-

He reports an F statistic for the overall goodness of fit, but fails to report the associated p-value.

No problem, we can hook him up right here:

$ pf(14.198, 3, 114, lower.tail = FALSE) [1] 6.333041e-08So that’s a lovely significance of p∼6.3×10−8.

- As far as effect size, and adjusted R2∼25.3% is also quite reasonable for noisy social data like this.

- We checked, and got similar results with a naïve OLS linear model.

-

- On the other hand, this is crazy! The dependent variable is the presence/absence of DOGE layoffs, basically coded as 0 or 1. One shouldn’t use a continuous predictor for a binary variable like that; it just makes no sense.

Really, one should use the absolute bog-standared method of logistic regression here. We’re predicting a binary outcome from continuous predictors. Logistic regression predicts the log odds ratio of DOGE layoffs from the other variables, e.g.,

log(PrWe’re going to do this in 2 phases:

- A preliminary stab at the problem, using all the data and all the predictors, just to see what happens. If we don’t get a good fit here, we stop.

- Crossvalidation (10-fold) and regularization by LASSO. This puts pressure on variable selection to use as few variables as possible, and to choose whatever gets the minimum error rate on a test set withheld during training. We hope here to get a model which is good in a principled way, and which somehow resembles the first model (i.e., naïve variable selection based on our intuition about the correlation matrix above wasn’t too terrible).

Ok, here’s the first phase of naïve logistic regression with neither crossvalidation nor regularization:

Call:

glm(formula = doge_layoffs ~ Perceived_Ideology_Estimate + log(Annual_Budget_USD) +

log(Total_Staff), family = binomial(link = "logit"), data = bonicaData)

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) -9.4165 2.8449 -3.310 0.000933 ***

Perceived_Ideology_Estimate -1.3391 0.3136 -4.270 1.95e-05 ***

log(Annual_Budget_USD) 0.2873 0.1518 1.893 0.058415 .

log(Total_Staff) 0.2001 0.1871 1.070 0.284681

---

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1

(Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

Null deviance: 141.71 on 117 degrees of freedom

Residual deviance: 107.04 on 114 degrees of freedom

(5 observations deleted due to missingness)

AIC: 115.04

Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 5

# R2 for Generalized Linear Regression

R2: 0.262

adj. R2: 0.248

- This says the regression coefficient for ideology was large in absolute value, and indeed quite significant with p \sim 1.95 \times 10^{-5}. So our intuition from the correlation matrix that this was a significant and strong predictor is confirmed.

- The regression coefficients for log of staff size and budget are not individually significant. This also confirms our correlation matrix inspired intuition.

- We used a

McFadden pseudo-R^2 (aka \rho^2)

as a measure of strength of effect, taking the place of Pearson R^2 in OLS. The

adjusted value of 0.248 is apparently pretty good, according to lore. McFadden’s book

is quoted on StackExchange in the preceding link as saying:

“… while the R^2 index is a more familiar concept to planner who are experienced in OLS, it is not as well behaved as the \rho^2 measure, for ML estimation. Those unfamiliar with \rho^2 should be forewarned that its values tend to be considerably lower than those of the R^2 index… For example, values of 0.2 to 0.4 for \rho^2 represent excellent fit.”

So this looks pretty good: an excellent fit by McFadden’s pseudo-R^2 criterion, emphasizing ideology score while reluctantly admitting a very slight effect for budget and staff size. (Though frankly, staff size had a bigger regression coefficient than I’d have initially thought. Ah, well: that’s why we do the statistics! As Montaigne would have said, it is “pour essayer mes pensées”, or “to try out my thoughts”.)

Now let’s try doing everything right (for once!). We’ll use the excellent glmnet library

to do both 10-fold crossvalidation and LASSO regularization. The former will keep us from

overfitting, and the latter will help us decide which predictors to take seriously, both

on an objective basis.

Everything is done as a function of the L1 penalty \lambda in the LASSO. Larger values of \lambda impose stiffer penalties, demanding removal of more variables. We pick the value of \lambda which results in the best crossvalidated error rate, i.e., prediction on a test set withheld during model building.

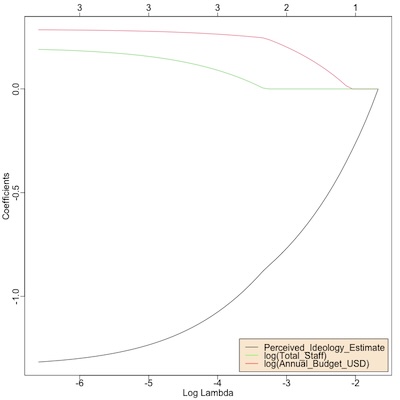

Here we see the 3 regression coefficients as a function of \log\left(\lambda\right).

Here we see the 3 regression coefficients as a function of \log\left(\lambda\right).

- For sufficiently large values of \lambda, all coefficients are eventually driven to 0 and we end up with just a constant term for prediction. That’s clearly too strict!

- For smaller (more negative) values of \lambda, more coefficients are allowed, and indeed can take on larger values, contributing more to the value being predicted.

The artful question then, is how to pick \lambda because that then tells us which levels of regression coefficients we should believe.

And that’s exactly the question addressed here in the next graph.

And that’s exactly the question addressed here in the next graph.

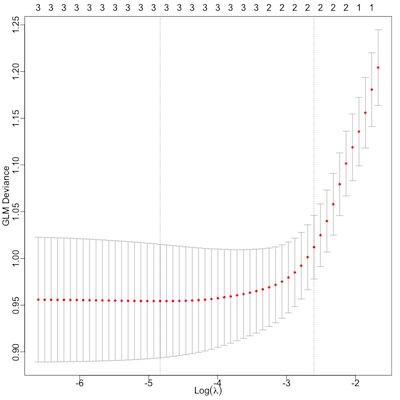

The vertical axis is the crossvalidated error rate (for a logistic regression model, “deviance”). The horizontal axis is \log\left(\lambda\right), the L1/LASSO penalty. Across the top of the graph, the mysterious integers are the number of parameters with regression coefficients allowed to be nonzero at that value of \log\left(\lambda\right). You can see it decrease from 3 parameters to 2 parameters to 1 parameter as we make the penalty more severe.

Obviously, we’d like the error rate to be small, and indeed as \log\left(\lambda\right) is relaxed we introduce more variables, allow their regression coefficients to become large, and the error rate goes down.

Up to a point!

The error does not decrease further below about \log\left(\lambda\right) = -4. Technically, the minimum is just around -5, where the vertical line indicates the “best” model with minimum error rate. But really, there’s a broad, flat plateau where the error rate is about the same. This “best” model is a 3-parameter model, using all 3 of our predictors.

There’s another vertical line at about -2.7. This is a heuristic, I think due to Hastie: find the “best” model, then find the simplest model that’s within about 1 standard error of the deviance. So instead of picking the technically best model, it picks the simplest model that is reasonably hard to distinguish from it. This model is a 2-parameter model, which has rejected one of our covariates. Based on the correlation (smallest correlation with DOGE layoffs) and the naïve regression above (least significant coefficient), we guess that it eliminates staff size.

The crossvalidated result from cv.glmnet() tells us the value of \lambda at those 2

points, the error rate, and the number of nonzero parameters:

> cv.glmMdl

Call: cv.glmnet(x = mx, y = foo$doge_layoffs, alpha = 1, family = binomial(link = "logit"))

Measure: GLM Deviance

Lambda Index Measure SE Nonzero

min 0.00795 35 0.9648 0.09234 3

1se 0.08140 10 1.0437 0.07921 2

Let’s see what those models are:

- The “best” model uses all 3 variables:

(Intercept) -8.6750538 Perceived_Ideology_Estimate -1.2165875 Annual_Budget_USD 0.2765157 (log value) Total_Staff 0.1495411 (log value) - The 1SE model (simplest one within 1 standard error of the best) uses 2, dropping staff:

(Intercept) -2.43285940 Perceived_Ideology_Estimate -0.46511838 Annual_Budget_USD 0.06741818 (log value) Total_Staff . (log value)

So which of these do we choose?

I’m slightly inclined – and I’m going completely on “vibes” here – to choose the “best” one. It looks very, very close to the naïve logistic regression we got above, the one with the “excellent” McFadden pseudo-R^2.

- Ideology score:

- The negative coefficient of ideology means when the ideology score is negative (“left”) the probability of DOGE firings goes up.

- The rather large value of the ideology coefficient means it’s making a big contribution to that judgment.

- The model somewhat reluctantly allows log staff size and log budget to come along for

the ride.

- Their positive values mean it’s slightly more likely that attacks happen in large agencies, either in head count or in budget. Those 2 are correlated, anyway.

- But they’re smallish values, not as significant, and contributed vastly less to the prediction of DOGE layoffs than ideology score. Indeed, if we accept Hastie’s 1SE heuristic, staff size drops out altogether and is represented by the budget size, with which it’s correlated.

The Weekend Conclusion

Summary: These firings are not directed at targets where a lot of money might be saved; they are directed according to the political tastes of those directing them. In other words, it’s revenge instead of governance.

The work of opposition is possibly unending. The work of reconstruction of democracy is daunting.

When overwhelmed, we might consider Sisyphus, condemned by the gods to pointless labor,

always failing. In The Myth of Sisyphus, the last sentence Camus has for us on the topic is:

When overwhelmed, we might consider Sisyphus, condemned by the gods to pointless labor,

always failing. In The Myth of Sisyphus, the last sentence Camus has for us on the topic is:

“Il faut imaginer Sisyphe heureux.” (One must imagine Sisyphus happy. I.e., the task of life itself must be a source of joy, even without success, and despite absurdity.) — Albert Camus, the last sentence of Le Mythe de Sisyphe (The Myth of Sisyphus)

So… one must imagine Sisyphus happy, for we are each of us living in Sisyphean times. Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal has the right of it, as shown here. [5]

I’m very sorry I have nothing better than that to offer you.

Please go do something wonderful and tell me all about it.

(Ceterum censeo, Trump incarcerandam esse.)

Addendum 2025-Feb-25: Predicting Layoffs, and Bayesian Performance

If you’re curious how, after all that fitting, one uses the model to make predictions,

here’s how! Of course the details are in the R script; see the function

confusionMatrix().

- Create a matrix of the input variables ideology, log staff, and lot budget for which you want predictions.

- Use the

predict()generic function on the fitted model, the matrix of inputs. Give it a value of \lambda and tell it you want the “response”, or probability, as the output.

The we make a confusion matrix, which is a 2x2 matrix with the actual DOGE layoffs on the rows, and the predictions on the columns, each cell containing an agency count. In an ideal world, this would be perfectly diagonal: the model would predict what happens, and no errors (off-diagonal elements) would occur.

For example, here’s the confusion matrices for the \lambda_{\mbox{min}} model with 3 coefficients:

lambda.min

doge_layoffs FALSE TRUE

FALSE 75 9

TRUE 18 16

There are 9 times the model predicted layoffs where there were none, and 18 times when the model predicted no layoffs but they happened anyway.

For comparison, here’s the confusion matrix for the simpler \lambda_{\mbox{1SE}} model about which I had a twitchy feeling:

lambda.1se

doge_layoffs FALSE TRUE

FALSE 84 0

TRUE 33 1

Note that this model has a very peculiar property: it almost never predicts layoffs, except in 1 case! Clearly this model has been regularized so violently by LASSO that it’s been hung by the neck until dead.

Our intuition to pick the \lambda_{\mbox{min}} model was correct.

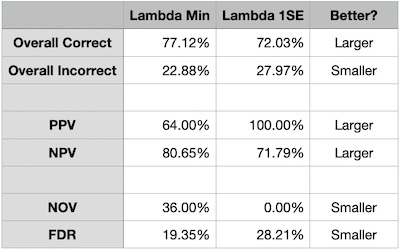

Now we can compute some probabilistic assessments of model performance.

First off, how often is it correct? This is an overall assessment, useful for telling if the model is doing anything but not of much practical use after that:

\begin{align*} \mbox{Overall correct} &= \Pr\left(\mbox{DOGE Layoffs & Model prediction agree}\right) \\ \mbox{Overall incorrect} &= \Pr\left(\mbox{DOGE Layoffs & Model prediction disagree}\right) \end{align*}Next, we’d like some Bayesian probabilities: given what the model predicts, what is the probability that the actual presence or absence of DOGE layoffs agrees? Those are, respectively, the Positive Predictive Value and the Negative Predictive Value.

Also, we’d like to quantify our errors. The Negative Overlooked Value is the chance there’s a layoff when we predict none, and the False Discovery Rate is the chance there is a no layoff when we predict one. (NB: Not the False Positive Rate, which is its Bayesian dual.)

\begin{align*} \mbox{PPV} &= \Pr\left(\mbox{DOGE Layoffs }\;\;\;\;\: | \mbox{model positive}\right) \\ \mbox{NPV} &= \Pr\left(\mbox{No DOGE Layoffs} | \mbox{model negative}\right) \\ \mbox{NOV} &= \Pr\left(\mbox{DOGE Layoffs }\;\;\;\;\: | \mbox{model negative}\right) \\ \mbox{FDR} &= \Pr\left(\mbox{No DOGE Layoffs} | \mbox{model positive}\right) \end{align*} So here are how the \lambda_{\mbox{min}} and \lambda_{\mbox{1SE}} models compare.

So here are how the \lambda_{\mbox{min}} and \lambda_{\mbox{1SE}} models compare.

By these measures, it appears the \lambda_{\mbox{1SE}} is a bit better in some ways, and a bit worse in others. However, if we had not looked at the confusion matrix above, we would not know that it makes only 1 prediction of layoffs! That is, the \lambda_{\mbox{1SE}} model barely does anything at all.

The \lambda_{\mbox{min}} model, using ideology, log staff, and log budget, does rather well.

- It’s overall right about 77% of the time, which is probably more often than I am overall right about anything.

- If it predicts layoffs, there’s about a 64% chance that’s true.

- If it predicts no layoffs, there’s about an 81% chance that’s true.

Overall, this is a credible model: it’s a good fit, and it makes reasonably correct predictions (without being spookily correct like overtrained models).

Notes & References

1: A Bonica, “Empirical Evidence of Ideological Targeting in Federal Layoffs”, BlueSky social media post, 2025-Feb-19. ↩

2: MD Richardson, JD Clinton, and DE Lewis, “Elite Perceptions of Agency Ideology and Workforce Skill”, Journal of Politics 80:1, 2018-Jan. DOI: 10.1086/694846.

NB: This article is regrettably paywalled. While there are ways around that, in this case, given Bonica’s good reputation, we’ll trust that he extracted the data properly and that the data is itself correctly constructed and relevant.

Fortunately, Bonica extracted the data and combined it with the DOGE firing data. We’ve archived a copy locally on this CLBTNR, below. ↩

3: Weekend Editor, “R script to analyze Bonica’s relation of department ideology to DOGE firings”, Some Weekend Reading blog, 2025-Feb-24.

The subroutine libraries graphics-tools.r and pipeline-tools.r are available from me,

upon request.

We’ve locally archived Bonica’s data in case the original disappears, and for ease of your peer review.

There is also a textual transcript of running this R script, so you can check it says what I say it says. ↩

4: JM Maher, et al., “The Other Half of the Story: Effect Size Analysis in Quantitative Research”, CBE Life Sci Educ 12:3, 2013-Fall, pp. 345-351. DOI: 10.1187/cbe.13-04-0082. PMID: 24006382. PMC: PMC3763001.

See, in particular, Table 2 on interpreting an odds ratio as an effect size. ↩

5: Z Weinersmith, “Hades”, Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal, 2019-Dec-28.

I particularly liked the comparison of the labor of Sisyphus to a Zen garden, and how it made Zeus (here apparently a deus otiosus or deus absconditus?) realize how bad things were in the mortal world. ↩

Gestae Commentaria

Comments for this post are closed pending repair of the comment system, but the Email/Twitter/Mastodon icons at page-top always work.